THE MACHINAFESTO: The Role Of Art In The Future Of AI

How a room full of artists, researchers, curators and technologists collaborated with a machine to produce a manifesto for human-computer art — and what it tells us about the future of AI, ethics, and human agency.

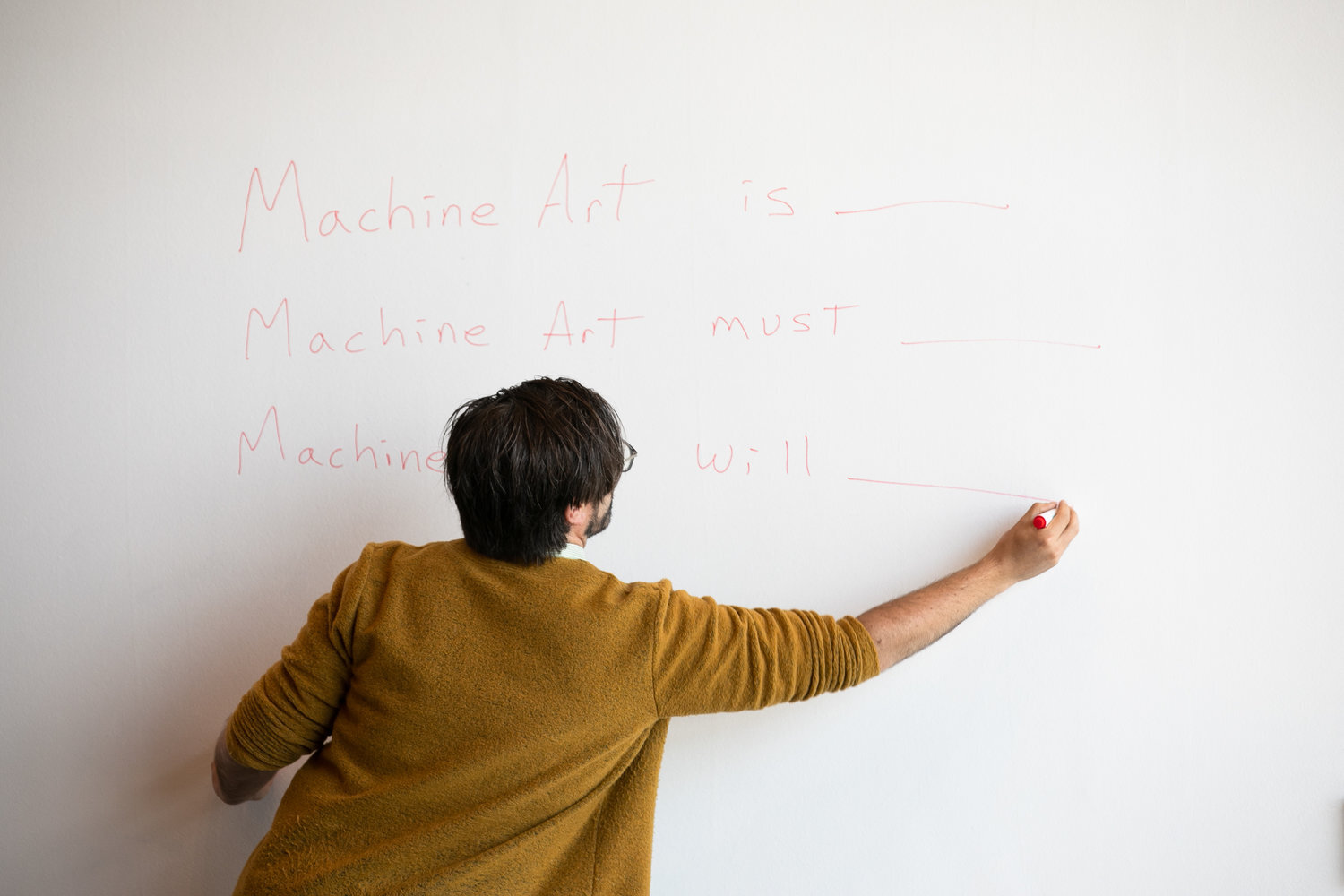

Eryk Salvaggio presenting prompts for the “Machinafesto,” a human-computer collaboration with the attendees of the “Machine, Myself & I” symposium at swissnex San Francisco on July 12, 2019. PHOTO MYLEEN HOLLERO / SWISSNEX SF.

As part of a swissnex San Francisco exhibition on AI-related art works, we invited several artists, critics, curators, and industry experts to come together for a daylong symposium on AI art. At the end of that session, the group co-wrote a “Machinafesto” that was then given to the GPT2 to create an extension of the Machinafesto, and wrote about it for nextrends, swissnex San Francisco’s online publication. I’m copying that text below.

With AI being such a wide-open landscape — and with consequences of abuse described as everything from perpetuating unfair discrimination (proven) to mass human extinction (unclear) — it’s important to engage with artificial intelligence from as many perspectives as possible, including informed voices that can see research and industry from the outside.

On July 12, 2019, we gathered thought leaders — academics, artists, activists, curators, industry, programmers, and researchers — for a day-long symposium, Machine, Myself & I, exploring the impact of machine learning and AI on our visual culture. The swissnex Gallery exhibition, An Eye Unruled, presents five artists that explore AI — either using AI to make work, or creating art that explores the history or speculates on the future of the technology: Gene Kogan, Simone C Niquille, Maria Guta, Dominique Koch and Pinar Yoldas.

Over the course of the session, we collected human statements about Machine Art, and these ideas became the source material for text-generation software Transformer, using the controversial GPT2 language model by OpenAI. A limited version of this model is accessible via TalkToTransformer. The model read our text, analyzed it, and then “predicted” the second half of the manifesto, essentially creating a half-human, half-machine declaration on the future of AI art: a “Machinafesto.”

You can read it below — and then read on for an explanation of how it works, and why advanced text generating tech such as GPT2 is so controversial.

The Machinafesto

Machine Art should not harm anyone.

Machine Art must embrace mistakes.

Machine Art will demand input.

AI will create glitches.

Machine art must develop empathy.

Machine Art must decentralize in the beginning, like building an airplane in the air.

Machine Art must be an independent artist.

AI Art must return to love.

Machine Art must be confused.

Machine Art is something like a child.

Machine Art must have a hive-mind.

Machine Art will lead our adoption of ethical language for technology.

Machine Art will reveal what we consider to be essential properties of being human.

Machine Art must struggle against the reification of standardization of one point of view.

Machine Art challenges our ideas of authorship, ownership, and identity.

Machine Art must be serendipitous.

Machine Art is a new aesthetic.

Machine Art is augmented creativity.

Machine Art is generated with human curation.

Machine Art is procedural, generative, algorithmic.

Machine Art is ASANE, not insane or sane (just like Amoral)

Machine Art is a collaborative performance.

AI Art is invested in process.

Machine Art will save us from our demise.

Machine Art will kill us all.

Machine art is not only about getting the machine to do, and thinking about doing what machine art should do.

Machine Art is a way to say that what you have is not something you are alone with.

Machine Art is for us to experience that which we are afraid of.

Machine Art is for humanists to know what we are. The art of Machine Art is not just about machine-like abilities. Machine Art can also be used to reveal the limitations of people's self-

Machine Art is a universal solution to the problems of the 21st century.

This is why Amoral is better than Machine Art.

Machine Art makes a difference, not only in the short run, but more importantly in the long term.

That is machine art that creates art, not art.

How It Works

Natural Language Processing is one of the most public-forward applications of AI — it’s baked into our smartphones as predictive text. Start typing a text message and you’ll see the machine sort out its best guess as to what the next word in your sentence will be.

The way this works is by building relationships between the words you use — that’s why “good” is more often paired with “bye” or “night” than, say, “octopus” or “hypotenuse.” As your text messages pile up, words get assigned weights in relationship, with the “heavier” words earning their spots as the next best guess.

The Transformer application is built on this idea, but instead of reading a word and guessing what comes next, it reads full sentences. OpenAI’s GPT2 technology was trained on massive amounts of high-rated internet conversations, pulling from sites like Reddit and Twitter to see which words are most closely associated in the English language. The result was designed to predict the next word, but it turns out to be impressively capable at generating sentences, paragraphs, and even whole news stories based on a single prompt.

This is a big deal — not only because it’s a huge step forward for language processing, but because this is tech that could simplify voice commands, read complex texts and create reliable summaries, and make “conversational” robots that understand the nuances of spoken language one step closer to reality.

To its credit, OpenAI has held back on releasing a full version of the model, fearing the ripe potential for abuse: imagine being able to generate a decade’s worth of fake news stories or fake research; or an entire fake history for a fake social media profile, complete with fake friends with their own history and fake networks. Consider the ability to create thousands of different texts, expressing the same sentiments, and submitting them to government review panels, or as letters to the editor, or as comments on a news site. It would make disinformation campaigns and propaganda bots even harder to discern from real human beings, shaping a false illusion of a public consensus, bringing chaos to public discourse and our faith in news reports and other media.

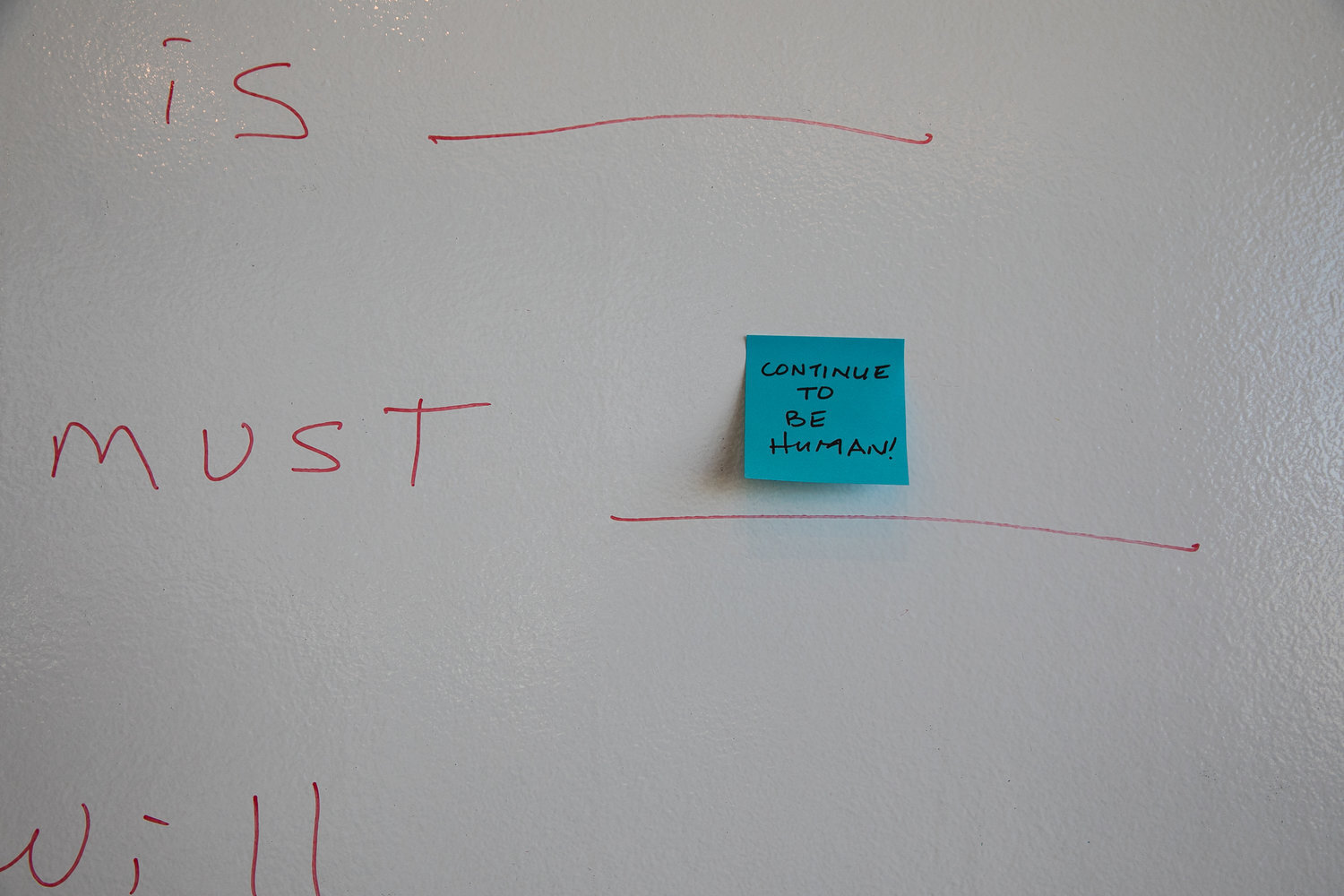

Various responses collected for the “Machinafesto,” a human-computer collaboration with the attendees of the “Machine, Myself & I” symposium at swissnex San Francisco on July 12, 2019. PHOTO MYLEEN HOLLERO / SWISSNEX SF.

In other words, it’s an AI that accelerates and augments what we already do — and sometimes, humans aren’t doing benevolent stuff. Understanding how AI works and how to spot it is critical — and art can play a role.

Creating the Machinafesto

The Machinafesto was envisioned as a playful, collaborative art project to help us see how textual AI — Natural Language Processing — works, and to better understand not only what it produces, but how we respond to that product.

Creating the machine-art manifesto required a collection of human-generated statements, each following a fill-in-the-blank format:

Machine art is ________.

Machine art must _________.

Machine art will _________.

This created a repeatable formula that would be easy for the AI to recognize, and recreate. Ideas were collected over the course of “Machine, Myself and I", a day-long symposium introducing AI-produced artworks from each of the An Eye Unruled artists; with an audience of artists, curators, ethicists, and researchers. In the end, 30+ participants filled in their own ideas in response to the prompts, informed by the program. This created the first half of the Machinafesto (which is a good read on its own).

Once completed, these human responses were “fed” as prompts to a Natural Language Processorr: an AI running a restricted, public version of the OpenAI text-generation platform, available online at TalkToTransformer (try it yourself!). From there, the machine was able to determine very easily what the “pattern” was, and begin to fill in blanks on its own.

Here’s the machine-generated portion of the Machinafesto:

Machine art is not only about getting the machine to do, and thinking about doing what machine art should do.

Machine Art is a way to say that what you have is not something you are alone with.

Machine Art is for us to experience that which we are afraid of.

Machine Art is for humanists to know what we are. The art of Machine Art is not just about machine-like abilities. Machine Art can also be used to reveal the limitations of people's self-

Machine Art is a universal solution to the problems of the 21st century.

This is why Amoral is better than Machine Art.

Machine Art makes a difference, not only in the short run, but more importantly in the long term.

That is machine art that creates art, not art.

What Did We Learn?

One of the patterns that is easy to recognize is a kind of “semantic drift.” Text-generating AI’s often come across like a teenager rephrasing the same idea to hit the required word count of their homework. The machine’s initial sentences are usually the strongest. But over time, they tend to lose their sense of focus.

One of the most impressive elements of the OpenAI platform was that it could read text and identify the subject, and remember that subject across a text. Consider a simple story:

My cat’s name is Bob.

Bob is gray.

He’s usually happy in the sunlight.

A human can tell that “Bob” is a “Gray Cat” and, because of the order of the information, we know that the “He” that enjoys the sun in sentence three is Bob the gray cat. The text predictor in your phone would have no idea that Bob is a cat; nor would it know that “He” refers to Bob.

Most text-generating software couldn’t tell, for example, what “it” or “she” or “he” refers to, but GPT2 has proven to be very good at maintaining attention. It can keep some degree of focus and apply it to predict the next sentence. It does this quite well initially, but can drift into more poetic, whimsical, and strange abstractions as it keeps writing.

For example, here’s what happens when I enter that series of sentences into the platform. Notice the drift from strange, childlike musings to downright weird:

My cat’s name is Bob.

Bob is gray.

He’s usually happy in the sunlight.

When the sun’s rising, he sits on the side of my front porch.

When it's setting, I walk Bob off to the back yard.

When he’s home, nothing.

I’d rather have Bob on my right side of the house than my left.

When I am in the yard at night, I turn my head.

He’s sleeping on the floor.

I donʼt know what kind of cat I am

I am a good listener and often look over his shoulder as his room closes.

What’s Next?

As we created the Machinafesto in collaboration with the machine, we kept in mind the challenge of human subjectivity around language: often, we stretch our intuitive understanding of language to accommodate what we think the meaning might be, as in the abstractions of poetry, or a conversation between two speakers in a language that isn’t native to either. But machines don’t have a hidden intent, or a sense of poetic abstraction. Decoding their language as poetry is tempting, but ultimately fruitless: what seems like metaphors, or challenging prose, is typically the result of word associations. What seems like a pun is, in fact, assigning the meaning of one word (such as apple the fruit) to another (such as Apple the brand). The result can seem playful, tempting us to project a human intelligence, even a sense of humor, into the output.

To understand the future, it might be best to understand the past. The first chatbot was a psychologist, ELIZA, which repeated key phrases entered into it, and rephrased them as questions back in the late 1960s. When its inventor, Joseph Weizenbaum, introduced this to a laboratory assistant — an assistant well-versed in computer science — the assistant nonetheless requested time alone with the machine, to really talk to it and see if it could help with their personal problems. This annoyed Weizenbaum, who was only ever to see the output as the completion of a computational command, executed well, or badly.

Weizenbaum later wrote about the phenomenon, comparing it to a tourist finding their way back to a hotel room, deciding to turn left or right by flipping a coin. Weizenbaum noted that the tourist could, in fact, arrive at their destination through this method — but it didn’t mean the method worked. Today, artificial intelligence’s coin tosses arrive at the destination more often than ever before — but we have to gird ourselves against attributing that to a consciousness, or even an understanding of language.

What’s next is — very likely — not an ongoing “collaboration” with technologies such as the OpenAI GPT2, but the challenging work of understanding how human minds respond to generated text; how we begin to read, think, and process what it’s telling us, and how to develop “filters” that protect us from ascribing a humanlike intent. To protect ourselves from the greatest manipulations of the next century, we have to think critically about AI-produced texts in a whole new way, one that overcomes our temptation to project meanings, thoughts, and feelings from an intelligence that doesn’t exist.

To prepare for the future of AI manipulation, we need artists to expose new ways of relating to machine intelligence, or more crucially, the illusion of machine intelligence. The Machinafesto was a playful attempt to understand how we engage with an artificial intelligence as a “collaborator,” including the allure of personification. In the end, these kinds of creative approaches can illuminate the gap between human and artificial intelligence — and the role humans play in filling those gaps, for better or for worse.

A human-submitted response for the “Machinafesto,” a human-computer collaboration generating an artistic manifesto, co-created with the attendees of the “Machine, Myself & I” symposium and the OpenAI GPT2 text-generating platform at swissnex San Francisco on July 12, 2019. PHOTO MYLEEN HOLLERO / SWISSNEX SF.

The result was a fascinating and sometimes surprising look at an entirely new approach to art, and, perhaps, even a new approach to artificial intelligence. (Just kidding — that last sentence was “predicted” by the GPT2 model in response to this article).

“An Eye Unruled” and the “Machine, Myself and I” program are presented in partnership with the #SwissTouch Campaign of Presence Switzerland, the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Création Baumann, the Canton de Vaud (DGES), the University of Lausanne, and Maison d’Ailleurs. The entire program was developed in collaboration with the Fotomuseum Winterthur, a leading Swiss institution for the presentation and discussion of photography and visual culture. The partner for bench coverings and curtains is Création Baumann, with its internationally renowned Swiss textile label.